A few weeks ago we opened our eyes to the ecosystems around and within us. We are natural, fluctuating systems, not static mechanical machines. We are a part of nature and nature is a part of us. There is no us without the World and the Sun—we are made of the elements and energized by light. We are individuals in families, communities, and local regional ecosystems. We are as much a part of the big picture as the big picture is a part of us. Now we get to dive further into looking at our health through the eyes of Chinese medicine.

I last talked specifically about Yin, Yang, and You in a newsletter on August 11, 2024. If you click on that title, it will take you to the post on my website if you want to see what we talked about then. Now, I want to get a little deeper into how Yin and Yang are used in Chinese medicine to look at, assess, diagnose, and treat disharmonies and disease. We’ll just scratch the surface here, but hopefully it will be a good start.

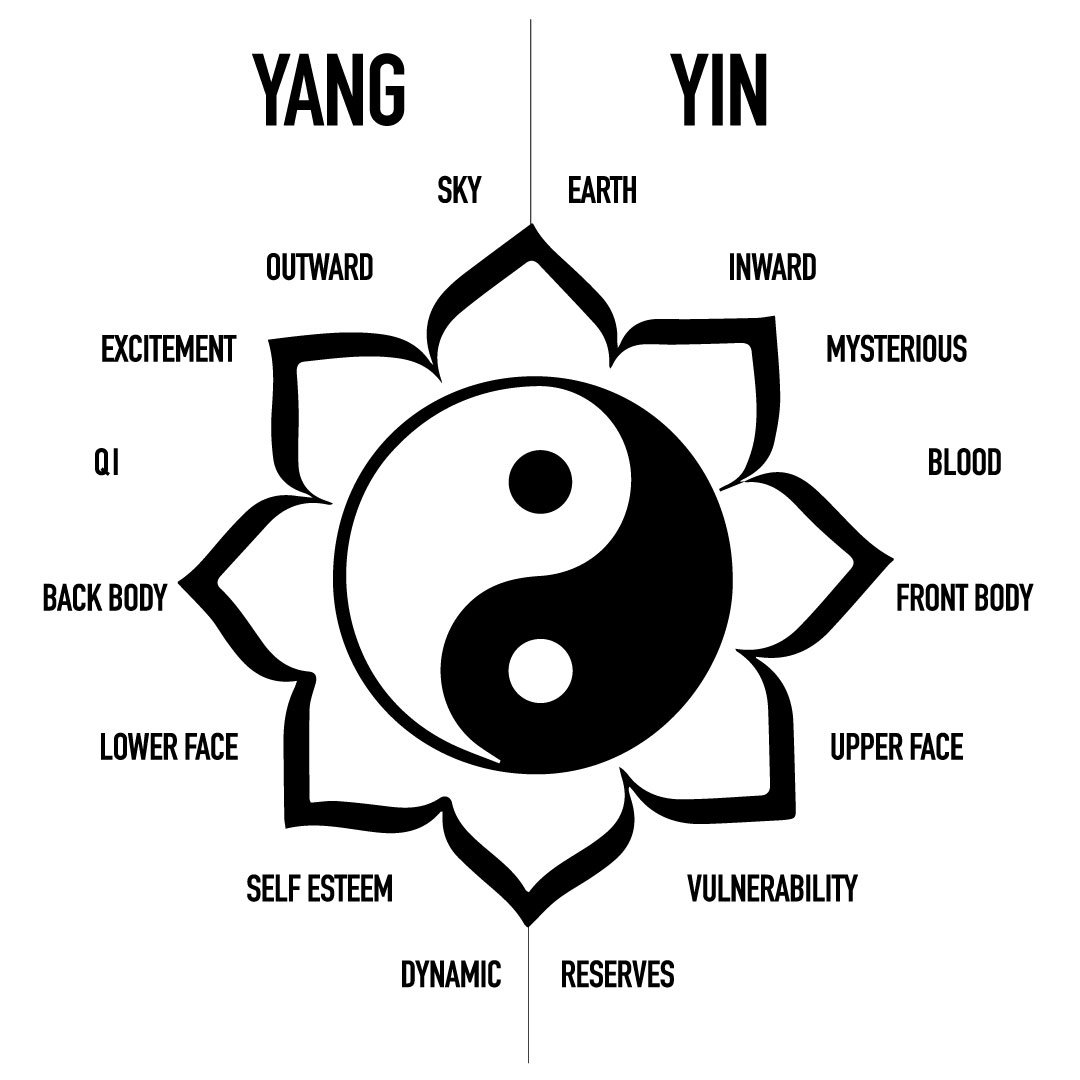

Yin-Yang theory is the foundation of the worldview that supports Chinese medicine. This is the understanding that everything can be seen as a combination of two aspects, one yin and one yang. Furthermore, every part can be divided into smaller parts, and these smaller parts themselves are yin and yang. For instance, looking at the solar system, Earth is yin to the Sun which is yang. However, when we look at the Earth as a whole, the deep inner core (interior) would be considered more yin, the surface (exterior) would be considered more yang. A river valley is considered more yin in relation to the mountains rising up from it. On our bodies the upper half including the head is considered more yang, and the lower half including the legs is considered more yin. The surface of our skin (exterior) is more yang, and the organs (interior) are considered more yin.

In general, when we look at anything we examine it in its relation to itself – which part is yin, which is yang, as well as in relation to the environment around it. Once we can see that yin-yang balance in its normal functioning, we can then assess where it is being dysfunctional and what could be put back in balance. For instance, our head is the most yang part of our bodies, yet when we get nasal congestion which consists of mucus and phlegm (which are both signs of yin), then we can see that the yang head has been clogged with thick yin. To treat this, we are going to focus both on clearing the damp yin from the head and on bringing clear yang to the head to replace it.

Other signs of pathological yin in the body are edema, bloating, heaviness, and other forms of congestion and mucus/ phlegm/ damp. Whereas someone suffering from a headache may in fact have too much yang in the head, and often the pathways at the base of the skull and the neck and shoulders are congested and tight and don’t allow the free flow of yang coming into the head to leave properly, so it ends up getting too hot (overfilled with yang) and feels as though it may burst. Other signs of too much yang in the body can be redness, rashes, and red coloration.

Thinking in Yin-Yang aspects

Let’s practice looking at the Yin and Yang aspects of things. We can start to get a more natural sense of them that way and a good understanding of Yin and Yang underlies a good understanding of Chinese medicine.

The Seasons: Summer is the most yang, winter is the most yin. As the seasons turn from winter into summer, they pass through spring. Spring, then, is yin turning into yang. After the height of summer, then yang starts to decrease and yin begins to increase. This passes us through autumn which is yang turning into yin. In winter, yin is at its maximum, yang is at its minimum—but yang is still present and will gradually start to increase the moment yin hits its maximum. This shifting back and forth from one to the other happens with everything. Day (yang) turns into night (yin) which then turns back into day (yang).

Fuel and energy: When we take a log and set it in the fireplace and set it ablaze, the log—being the fuel—is the yin aspect of the equation. The fire—which uses the log as fuel to burn long and bright—is the active yang. Yet, if we wait long enough, the log will be consumed by the fire and then the fire will go out. No fuel (yin), no fire (yang). Our bodies are like this too in that we are made of substances and material that fuel the impulses, reactions, and cycles of movement our bodies make inside and out. Yet we cannot be only active, our bodies need rest and so we sleep to replenish ourselves. You could be an amazing athlete, but if you don’t eat, drink, and rest, then your athleticism will cease. Too much yang activity will consume our substantial yin.

Heat and coolant: Although I don’t think it’s good practice to only look at ourselves as engines, an engine provides a good metaphor for the need for balance in yin and yang. A motor engine burns fuel (yin) to make explosions (yang) that propel pistons around a driveshaft. But, as the engine runs, the heat from the explosions (yang) would flare out of control if left to their own devices and the engine itself would be consumed through heat (yang) by the process. This is why the radiator and engine coolant are so important. They are the yin that keeps yang in check. The engine coolant keeps the engine cool with a yin substance that is not consumable. As long as the coolant exists and flows around the engine, it will keep the yang from burning out of control. However, if the radiator or a hose gets a leak and the engine loses coolant, at some point the engine will overheat and need to be shut down. Our bodies are the same. Our yin also acts as a coolant against both the internal metabolic actions in our organs, and as a coolant against the heat of the environment. If people lose too much weight, then they do not have enough coolant to regulate their temperature and will find themselves too hot in the summer (not enough yin-coolant to keep them cool), and cold in the winter (not enough yin-fuel to stoke their internal fires to keep them warm).

Try to practice looking at things with an eye for the Yin and Yang of them and you’ll soon get the hang of it. Although concepts that underlie Chinese philosophy and medicine often seem confusing at first, they arise from observation of us in nature and are actually deeply intrinsic to the way we naturally live in the world. A great overview of yin and yang theory is here on the TCM World Foundation website. If you have a deeper curiosity about the history of yin and yang you can read through the Wikipedia entry on Yin and Yang here. And if you’d like to see how yin-yang theory can contribute to diagnosis in various medical dysfunctions, Dr. Peter Sheng has some examples here.